Nothing to Wear

Put on the full armor of God, so that you can take your stand against the devil’s schemes. Ephesians 6:11 NIV

Full armor – Body armor. Every civilization has some form of personal physical protection. Paul uses a term that was quite familiar to his audience. After all, they observed the Roman legionnaire’s equipment daily. The Greek term panoplía “is used variously for the soldier’s full equipment, for war material, for booty, and for the prize in contests. The only figurative use is in the biblical field.”[1] But there is a mythology behind this that we need to appreciate. Oepke notes:

The idea of invincibility because of divinely given weapons is an ancient one (cf. Odin’s helmet as a cap of invisibility, or Achilles’ armor, or Siegfried’s sword). In the OT God protects his people with his own weapons (cf. Pss. 7:11ff.; 35:1ff.). His faithfulness is a shield and buckler (Ps. 91:4). He gives power to the javelin of Joshua (Josh. 8:18, 26). The concept is moralized in the Iranian sphere. Philo believes that God has given rational speech to humans as a protection.[2]

panoplía in the NT. The word is used only figuratively in the NT. Luke has it in the parable of the overcoming of the strong man in 11:22. It occurs twice in the allegory of the Christian’s spiritual armor in Eph. 6:10ff. Here Paul takes his verbs from military speech, and he lists six items of equipment, i.e., girdle, breastplate, shoes, shield, helmet, and sword. He has in view the actual equipment of the Roman soldier along with OT models. Since the enemy is spiritual, the whole panoplía of God is needed. The background is the mythological one of God giving his own equipment, but the concept is spiritualized. In an ethical context, the apostle is describing a religious and moral battle. The weapons, however, are not moral qualities but divine realities. One’s whole existence depends on the outcome of this battle with the forces of evil, and one can triumph in it only in the Lord and the power of his might (v. 10).[3]

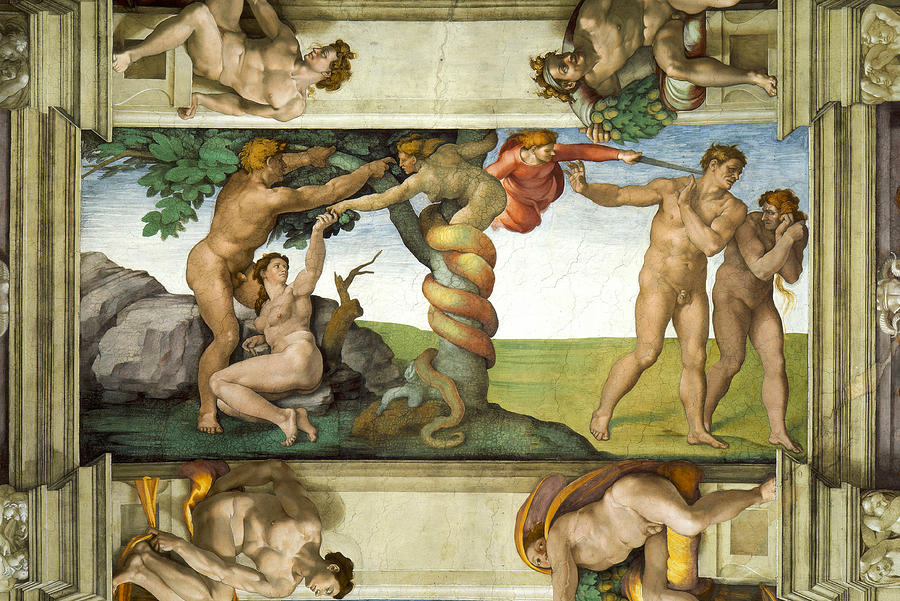

Contrast this with the Genesis account of the creation of human beings. Neither Adam nor the woman needed body armor. In fact, every painting of the creation portrays them nude, like this representation by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel:

Body protection (clothing) only became necessary after their sin. Why? Perhaps it isn’t really about being naked. As Adam discovered, fig leaves don’t really do the job. When Adam attempted to sew fig leaves for coverings, he was trying to conceal something, but it wasn’t his genitals. It was his disobedient pride. In Genesis 3:7 the word for “leaves” is ʿāleh, but the root isʿālâ which is almost always associated with what goes up (e.g., the smoke of a whole burnt offering) or what is high, what ascends, or upper, higher. The reason it’s translated “leaves” because of the next word, tĕʾēnâ, meaning “fig tree.” While the translation is probably correct, the nuance isn’t about leaves at all. It’s about something that ascends. Richard Davidson suggests that this allusion is about the cognate in another ancient language that describes a warrior’s belt decorated with the fame of his battles; in other words, a belt that displays pride.

The Hebrew word for loin covering is ḥagore’, from the root ḥāgar. The verb means “to gird, to put on a belt.” But the pictograph really tells the story. It means, “to make private (by fencing) the pride of a person.” One of the cognates of this word in Babylon is a military belt that served no useful purpose except to show off the status of the person. It was a belt of pride in prominent display.

We should notice that the Hebrew word pride (from the root ga’ah) means, “to rise up, to be lifted up or exalted.” If we read the story carefully, we see that Adam never asks forgiveness. In fact, he never even mentions his action. This implies that Adam wasn’t concerned about concealing his genitals. After all, he had always been naked (the symbolic representation of transparency). What Adam wished to conceal from the eyes of the Lord was the shift in the relationship. He wanted to put a fence around his self-exaltation, to cover his rising up against God’s command. The verb ga’ah paints the picture, “what comes from the lifting up of strength.” Adam discovered, much to his chagrin, that lifting himself up produced the necessity of privacy. Once his true identity could be openly displayed. Now it had to be concealed. “The things which man did lose were the glory of God and the dominion over nature which were associated with that image; he lost them when he forgot that he himself was the eikon theou [image of God] and sought to find that eikon [image] elsewhere. In doing so, he took on the image of corruption and became subject to death thus obscuring the fact that he was originally created in the image of the incorruptible God.”[4]

Once Adam was undressed. Now he needed psychological protection symbolized in covering “private” parts of the body.

Paul knew this story about Adam. Don’t you suppose that along with the common reference to Roman armor he might have had Adam’s covering in mind? After all, what is the “full armor of God”? It’s certainly not literal shields, breastplates and swords. In the battle Paul has in mind, those are entirely useless. But Paul does insist on armor, something Adam felt he needed too. The difference is that Paul’s armor is exactly the opposite of Adam’s ʿāleh tĕʾēnâ. It’s not the covering of pride. It’s the nakedness of humility. It’s not cloaking our sins. It’s exposing them. The fully armored man of God isn’t hiding anything, especially from his Maker. He doesn’t try to run, even if he’s “damaged goods.” He is what he is—undressed before his God.

Maybe we need a Hebraic “covering” for a Greco-Roman word.

Topical Index: fig leaves, pride, covering, armor, ʿāleh tĕʾēnâ, panoplía, Genesis 3:7, Ephesians 6:11

[4] Morna D. Hooker, Adam to Christ (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge), 1990, p. 83.

[1] Kittel, G., Friedrich, G., & Bromiley, G. W. (1985). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (p. 703). Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.