Introductory Matters

Prayer of an Afflicted Man for Mercy on Himself and on Zion. A Prayer of the afflicted when he is weak and pours out his complaint before the Lord. Psalm 102 NASB

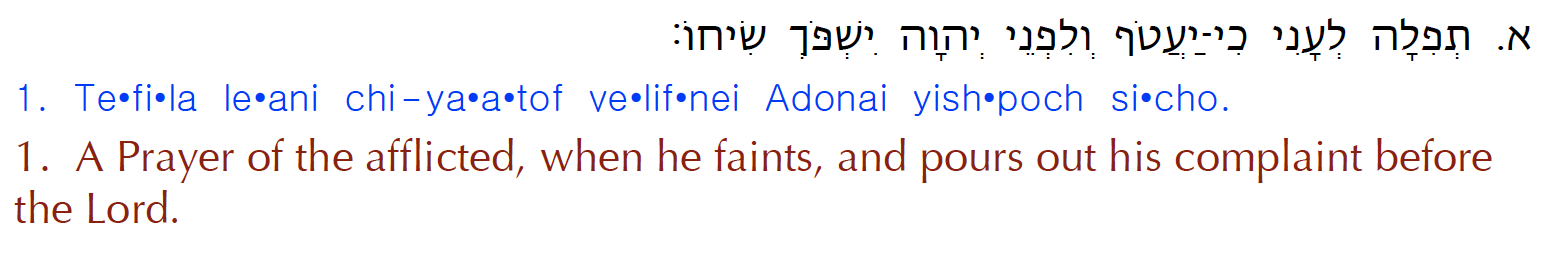

Prayer – In the NASB, these two statements have no verse numbers. They are treated as introductory summaries before the text of the actual Psalm. Of course, in Hebrew, at least one of these is incorporated into the psalm itself, as you can see here:

Apparently, the first “introductory” title (“Prayer of an Afflicted Man for Mercy on Himself and on Zion”) is an explanation derived from the LXX by the translators of the NASB. This highlights Robert Alter’s claim, “ . . . the translators are unwilling to trust the Hebrew and repeatedly feel the need to explain it or in some way embellish it.”[1] It seems that the translators of the LXX did the same thing as many modern translations. Old habits die hard.

The second introductory claim is, in fact, a part of the original psalm, not merely a sidebar declaration. So, let’s start at the real beginning.

A prayer of the afflicted, when he faints [is weak] and pours out his complaint before the Lord.

“A prayer” is the Hebrew word tĕpillâ. Only five psalms[2] are specifically called “prayer.” We might wonder why. After all, all the psalms are, in some sense, prayers. We use them that way today, and even if they were originally lyrics set to ancient music, it seems that the emotional draw of these ancient texts usually encourages some prayerful state. Why are there only five that specifically use the word tĕpillâ in the title? Let’s consider what these five are about.

Psalm 17 – a petition for God’s justice and protection

Psalm 86 – a petition for mercy in times of affliction

Psalm 90 – a cry for God to spare the people from His wrath and return them to favor

Psalm 142 – a cry for God to protect me from my enemies

We might also notice that in each of these psalms the initial state of desperation and affliction is resolved in an exhortation to the faithfulness and sovereignty of God. The pattern is more or less like this:

- I am afflicted by outside forces

- I need divine help

- You, Lord, are the true refuge and strength

- Overcome my enemies and restore me

- You alone are worthy of praise

So we have five psalms that are specifically about rescue through God’s strength. What is interesting is that the verbal root of tĕpillâ is usually the Hithpael, a reflexive form, that is to say, the verb looks back on the action as applied to the speaker. It is as if I were to say, “I myself am pleading for myself.” The very use of the word tĕpillâ indicates how personal the lyrics are, and since Hebrew has a dozen words for prayer, the use of tĕpillâ ensures that the reader will recognize the intense personal nature of these five. There are many, many psalms regarding Israel and the people of Israel, but in these cases, it is the author himself who begs for help—help based on an intimate relationship with his God. This is spiritual quid pro quo.

Perhaps we need to pause right at the beginning of this psalm, for unless it is personal for us, we will probably miss the pathos of the psalmist’s cry. Before we even get to the first exclamation, the mood is set. This is intimate agony. It doesn’t have to be a loud burst in the public arena. This is the tear-filled murmuring of a man at the end of his rope. When we read the lines, if we’re in touch with the author, the words will be written with teardrops. Otherwise it’s just one more line of black ink.

Topical Index: tĕpillâ, prayer, Psalm 102

[1] Robert Alter, The Art of Bible Translation (Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 58.

[2] Ps 17, 86, 90, 102, 142