A Little Change Here, a Little Change There (5)

You favor man with perception and teach mankind understanding. Grant us knowledge, understanding and intellect from You. Blessed are You, Adonoy, Grantor of perception. Amidah (Ashkenazi version)

Wisdom, intellect and knowledge – The Sephardic version of the Amidah reads as follows:

You favor man with knowledge and teach mankind understanding. Grant us wisdom, intellect and knowledge from You. Blessed are You, Adonoy, Grantor of perception.

The Ashkenazi word order is radically different, including the substitution of ḥokmâ (understanding) for haśkal (savvy). This is not a scribal mistake. It is deliberate. What we want to know is why.

First, we need to know the difference between ḥokmâ and śākal? Perhaps that will explain why the Sephardic version substitutes words. śākal is insight, savvy, intelligent use. ḥokmâ is from the verb חָכַם (ḥākam) be wise, act wise(ly).[1] “Of all the words denoting intelligence, the most frequently used are this verb and its derivatives, . . .”[2] “The verb bîn is used more widely to mean ‘consider,’ ‘discern,’ ‘perceive,’ but the nouns are close synonyms to ḥokmâ . . .”[3] “The root śākal is also widely used for ordinary intelligence and skill. It is often used for that wisdom which brings success—even prosperity.”[4] We discover that śākal has a double meaning: wisdom and success. Our choice of “savvy” is probably correct. ḥokmâ, on the other hand, “represents a manner of thinking and attitude concerning life’s experiences, including matters of general interest and basic morality. These concerns relate to prudence in secular affairs, skills in the arts, moral sensitivity, and experience in the ways of the Lord.”[5] Nevertheless, ḥokmâ still retains the nuances of shrewdness and prudence. It also emphasizes the fact that the source of all wisdom is God. One other element is important. “The ideal of the ḥkm concept finds expression in the calls to be wise, which make exhortation a dominant concept. . . There are also exhortations to teach wisdom, which promises particular success when the wise are involved.”[6]

The central role of ḥokmâ can be seen in the following citation, noting in particular the difference between Greco-Roman (Hellenistic) thought and ancient Hebrew thought:

The wisdom of the ot however, is quite distinct from other ancient world views although the format of wisdom literature is similar to that of other cultures. Reflected in ot wisdom is the teaching of a personal God who is holy and just and who expects those who know him to exhibit his character in the many practical affairs of life. This perfect blend of the revealed will of a holy God with the practical human experiences of life is also distinct from the speculative wisdom of the Greeks. The ethical dynamic of Greek philosophy lay in the intellect; if a person had perfect knowledge he could live the good life (Plato). Knowledge was virtue. The emphasis of ot wisdom was that the human will, in the realm of practical matters, was to be subject to divine causes. Therefore, Hebrew wisdom was not theoretical and speculative. It was practical, based on revealed principles of right and wrong, to be lived out in daily life.[7]

Finally, and significantly, Sephardic Judaism was highly influenced by Kabbalists.

After the expulsion from Spain, the Sephardim took their liturgy with them to countries throughout the Arab and Ottoman world, where they soon assumed positions of rabbinic and communal leadership. They formed their own communities, often maintaining differences based on their places of origin in the Iberian peninsula. In Salonica, for instance, there were more than twenty synagogues, each using the rite of a different locality in Spain or Portugal (as well as one Romaniot and one Ashkenazi synagogue).

In a process lasting from the 16th through the 19th century, the native Jewish communities of most Arab and Ottoman countries adapted their pre-existing liturgies, many of which already had a family resemblance with the Sephardic, to follow the Spanish rite in as many respects as possible. Some reasons for this are:

- The Spanish exiles were regarded as an elite and supplied many of the Chief Rabbis to the countries in which they settled, so that the Spanish rite tended to be favoured over any previous native rite;

- The invention of printing meant that Siddurim were printed in bulk, usually in Italy, so that a congregation wanting books generally had to opt for a standard “Sephardi” or “Ashkenazi” text: this led to the obsolescence of many historic local rites, such as the Provençal rite;

- Joseph Caro‘s Shulḥan Aruch presupposes a “Castilian rite” at every point, so that that version of the Spanish rite had the prestige of being “according to the opinion of Maran”;

- The Hakham Bashiof Constantinople was the constitutional head of all the Jews of the Ottoman Empire, further encouraging uniformity. The North Africans in particular were influenced by Greek and Turkish models of Jewish practice and cultural behaviour: for this reason many of them to this day pray according to a rite known as “minhag Ḥida” (the custom of Chaim Joseph David Azulai).

- The influence of Isaac Luria‘s Kabbalah.

The most important theological, as opposed to practical, motive for harmonization was the Kabbalistic teachings of Isaac Luria and Ḥayim Vital. Luria himself always maintained that it was the duty of every Jew to abide by his ancestral tradition, so that his prayers should reach the gate in Heaven appropriate to his tribal identity. However he devised a system of usages for his own followers, which were recorded by Vital in his Sha’ar ha-Kavvanot in the form of comments on the Venice edition of the Spanish and Portuguese prayer book. The theory then grew up that this composite Sephardic rite was of special spiritual potency and reached a “thirteenth gate” in Heaven for those who did not know their tribe: prayer in this form could therefore be offered in complete confidence by everyone.[8]

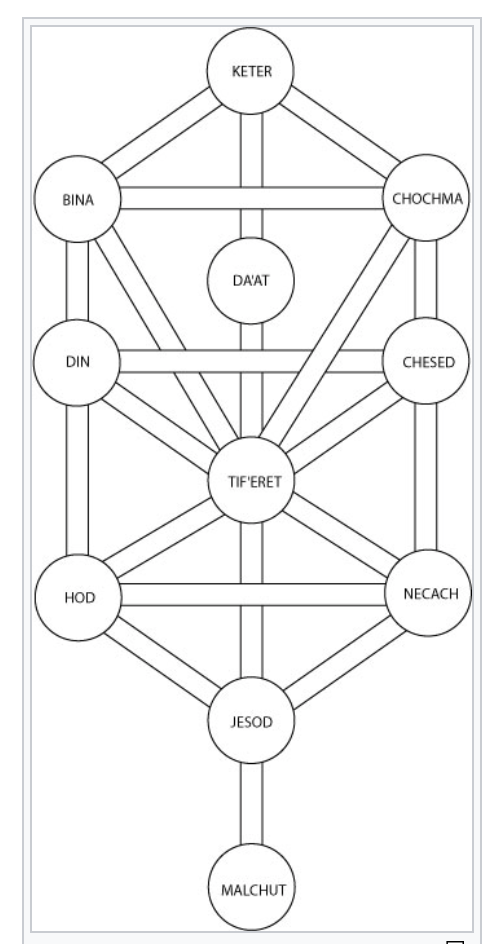

Kabbalah emphasizes the utter transcendence of God in His essence. This means we as human beings cannot know anything about His limitless simplicity. But God is also apprehended in what He creates and sustains. This aspect shows itself dynamically in the interaction between spiritual and physical existence, revealing the way God is manifested in the ordinary life of man. These emanations are called sephirot. “The Sephirot (also spelled “sefirot”; singular sefirah) are the ten emanations and attributes of God with which he continually sustains the existence of the universe. The Zohar and other Kabbalistic texts elaborate on the emergence of the sephirot from a state of concealed potential in the Ein Sof until their manifestation in the mundane world.”[9]

These emanations are connected like branches of a tree in the following way:

You will notice that our three words are connected at the top of this diagram, ḥokmâ – bin – da’at, with da’at as a central part of the middle chain and ḥokmâ and bin at the right and left, all three as the highest level just below Keter. “Keter is so sublime, it is called in the Zohar ‘the most hidden of all hidden things’, and is completely incomprehensible to man.”[10] Since it is unknowable to man, the highest forms of human knowledge are ḥokmâ, bin, and da’at. You will notice that (reading right to left – Hebraically) the order appears precisely as it does in the Sephardic version of the Amidah blessing. This explains, perhaps, why da’at is substituted for śākal. It also helps us understand how Kabbalah influenced the order of the words, since ḥokmâ, the highest level of knowing, was granted (gifted) to Man directly in the creation, and bin was the transmission of that knowledge to other men, resulting in da’at, in Kabbalistic thought, “the third and last conscious power of intellect. . . Da’at is associated in the soul with the powers of memory and concentration, powers that rely upon one’s ‘recognition’ (hakarah) of, and ‘sensitivity to’ (hergesh), the potential meaningfulness of those ideas generated in consciousness through the powers of Chokhmah and Binah “understanding”.[11]

Perhaps we have come across an explanation why the Ashkenazi and Sephardic versions differ. History, culture, and religious community made changes; changes that are followed today without conscious appreciation of their origins. Lighting the Shabbat candles and saying certain prayers on Shabbat also comes from Kabbalah systemization, although few participants actually know that these days. The culture absorbed the ideas long ago. Now they are de rigueur, like so many other religious practices.

Topical Index: Amidah, Sephardic, Kabbalah, ḥokmâ, bin, da’at

[1] Goldberg, L. (1999). 647 חָכַם. R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer Jr., & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 282). Chicago: Moody Press.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] P. Müller, TDNT, Vol. 4, p. 374.

[7] Goldberg, L. (1999). 647 חָכַם. R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer Jr., & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 283). Chicago: Moody Press.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sephardic_law_and_customs#Lurianic_Kabbalah

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabbalah#Concealed_and_revealed_God

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keter

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Da%27at

An enlightening summary of the historical development of the major Jewish traditions. What strikes me is: 1) God’s self-revelation is retained in both major Jewish traditions as the testimony of Israel’s faith; 2) there are similarities of these processes (collecting, preserving, and sharing Israel’s testimony of faith) with those evident subsequent to the advent of Yeshua of Nazareth; 3) while such influences are apparent, the testimony of witness retains consistency in its material presentation of witness, despite the variorum of variant textual readings.